Dutch Tilders

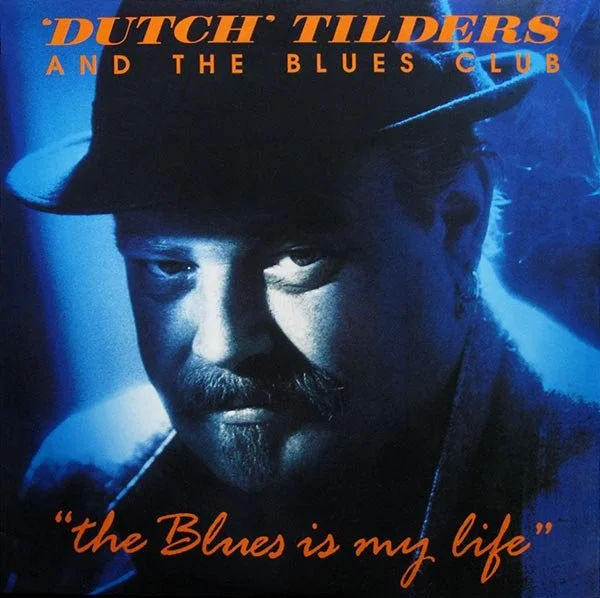

Album cover portrait “The Blues Is My Life“ 1990

Dutch Tilders was the warm-up act for John Mayall’s tour of Australia, in October 1974. It was the first time I had heard him play, and at first I felt a little impatient, wanting to hear Mayall’s band. That was until Dutch sang! The sheer power and clarity of his voice was quite astounding, and his acoustic guitar work was excellent. I cannot recall the song-list, though it consisted of several blues standards, and may well have included a couple of original compositions. Mayall’s vocal efforts were feeble, by comparison, and save for the amazing guitar-work of Freddy Robinson, his performance was something of a disappointment. Freddie really got into stride with a rocking solo, but Mayall cut him off. I had the distinct impression that Mayall did not want to be upstaged.

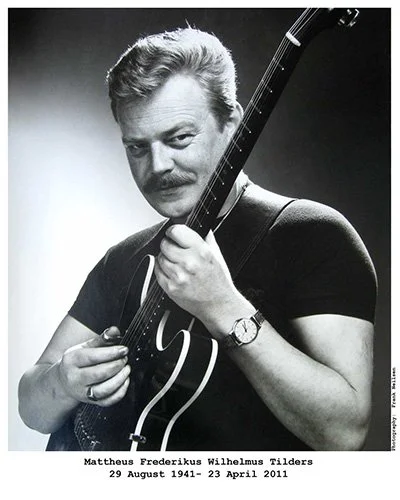

‘Dutch’ was a nickname for Mattheus Frederikus Wilhelmus Tilders, who had migrated to Australia with his family in 1955, as a fourteen-year-old. He bought his first guitar in 1959, and taught himself a lot about the English language by listening to American blues musicians. That way, he managed to develop a distinct American accent.

In 1981, my wife and I were invited to Dutch’s 40th birthday party. I was in a silly frame of mind that night, and decided to turn up wearing a tuxedo and rubber thongs. I was introduced to Dutch, who seemed quite ‘stand-offish’. He was accompanied by a beautiful blonde surfer girl from Queensland, Suzanne Petersen, who he would eventually marry. Suzanne was a lovely flautist. A few years later, after a strong friendship had developed, Dutch told me that he had thought I was a ‘poofter’ at that first meeting.

He was very happy to become godfather to our first daughter, and was unstinting in entertaining little kids at parties, with a seemingly endless collection of children’s songs. If there was a guitar in the house, Dutch would happily play for hours. During times of sadness, he was also willing to help. At my request, he sang ‘Saint James Infirmary’ at the funeral of my father-in-law. It was my favourite song from Dutch’s huge repertoire. He was accompanied by another close friend, jazz trumpeter Ian Orr, in a very clever arrangement of Sam Theard’s 1929 song ‘I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead’. It was recorded by Louis Armstrong in 1931, and was alternatively titled ‘You Rascal You’. Dutch had re-jigged the lyrics overnight, and sang ‘Glad to know you for a while, you rascal you…’ to floods of tears all round.

Dutch was a true raconteur, generally aided by large quantities of Heinekin Lager and Camel cigarettes. He loved telling jokes, particularly the shaggy dog variety. He could stretch a yarn out for hours, or even until the next time we met, making it seem like an absolutely true story. When the punch-line eventually came, it was generally met with groans, and laughter.

He had a searching intellect, and an ability to talk about any subject one could raise, even though a lot of it was quite facetious. I met up with him in the bar of the Windsor Hotel one afternoon, as a man was thanking him profusely for helping him with a problem. He told me afterwards that he had convinced the guy to get rid of his entire flock of homing pigeons, and trade them for a different breed. He knew virtually nothing about pigeons, but knew just enough to speak with what seemed like great authority on the subject.

His musical collaboration with leading musicians such as Brian Cadd and Kevin Boritch produced some legendary recordings, and his direct-to-disc album ‘Direct’ was a magnificent effort. He was always working with players at the top of their game, and worked with some great configurations of horns and keyboards.

He had a very long friendship with Tennessee-born bluesman, the wonderful Brownie McGhee, who we had the pleasure of meeting during one of his Australian tours. Dutch regarded Brownie as his true mentor.

Dutch was a stickler for correct, original lyrics. For instance, he always sang the final lines of Leadbelly’s ‘Goodnight Irene’ as ‘And if Irene turns her back on me I'll take morphine and die’. Leadbelly was the first man to record the song, and these lines are often omitted in other covers. Dutch also wrote many autobiographical songs, many of which were humorous, talking about about smoking, drinking and womanising.

Along the way, I photographed Dutch many times as promotional material for his shows. One particular poster was promptly stolen from pretty well everywhere it was displayed. We had printed hundreds, but ran out of them.

The Dutchman

In April 1990, Dutch released what was to win an award as Blues Album of the Year. ‘The Blues Is My Life’ was the work of ‘The Blues Club’, the core of which was the brilliant young guitarist, Geoff Achison, bass-player Barry Hills and drummer Winston Galea; a very powerful combination. Dutch won many awards for his music.

The Blues Club: Barry hills, Winston Galea, Geoff Achisomn, and ‘Dutch‘ Tilders, at the Windsor Hotel, Melbourne

In the spirit of the troubadors, Dutch had a devout following in any town he chose to visit, anywhere in Australia. He became known as ‘The Godfather of Australian Blues’.

After our family had moved to a regional town, Dutch was always a welcome guest in our house, whenever he was in town for various gigs. In about 2009, I noticed that Dutch had lost a lot of weight, and his previously muscular arms had become alarmingly thin. Shortly thereafter, he was diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus.

Aware of his fate, in August 2010 he released one last album, ‘Going On A Journey’, which is a real tour-de-force. It features many of Australia’s leading blues performers.

In July 2010, a benefit concert was held at the Thornbury Theatre in Melbourne, which was attended by hundreds of adoring fans, and many of his old musical collaborators, including his old friend Kevin Boritch. A very moving event, at which Dutch put on a sterling show, despite the gravity of his illness. He died on 23 April 2011.

His motto was “Keep the Faith”. His is an enduring influence on Australian blues music.

Please Note: A limited edition of 35 museum-quality prints of the main image (above) is available from our Shop.

Dutch’s funeral gig was huge!

For the technically-minded:

The imain mage was shot for the cover of ‘The Blues Is My Life’. I shot it in my studio with a Nikon F5 and an f4 80-200 Nikkor zoom lens. It was lit with Elinchrom studio electronic flash heads on Agfapan 100 black and white film, developed in Agfa Rodinal.

A 20” x 16” print was made, and that was lit with a mixture of white flash and blue gels, which was then shot onto 10” x 8” Ektach