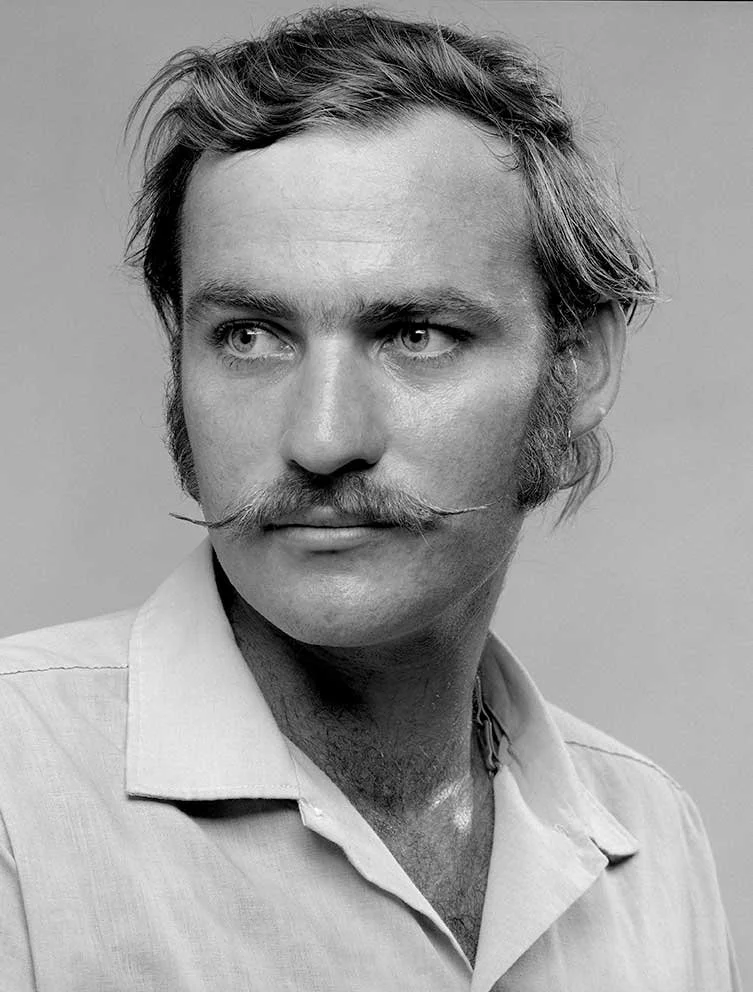

MIKE TATE

Michael Tate c. 1970

Michael Tate, my dear friend, was a tormented soul. Only a few readers will have heard of him. We met at Cavendish Road State High School in Brisbane at the end of 1961. About three years earlier, his alcoholic father had walked out on the family, and his mother had died of cancer. Mike, at twelve years of age, and his younger brother, were left in the care of his grandparents. His brother had suffered brain damage in utero, due to cancer treatments his mother was receiving.

Mike’s schoolwork naturally suffered, and he was kept down in Year 11, where we ended up in the same class. Kids who were kept down were generally thought of as being not too bright, but that certainly did not apply to Mike.

He was a prolific writer of poetry, and was an avid reader. By the age of fifteen, he had read, and understood, many of the dense works by writers such as Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Camus, de Sade, Sartre, Beckett, Orwell and Kerouac; as well as poets such as Behan, Yevtuschenko and Baudelaire. He was the first person to make me aware of Zen Buddhism. In art classes, he proved to be a natural-born dadaist, producing works of fantasy with a deeply cynical tinge.

We became members of P.E.N. (Poets, Essayists and Novelists) Junior, which held weekend meetings at various member’s houses. That was a refreshing way to meet people of like mind, several of whom remain close friends to this day.

Mike’s first job, fresh out of school, was with the Australian Department of Customs and Excise, where he eventually tired of spending all day stamping bits of paperwork, and had decided to seek a bit of adventure. He was working as a rigger with an oil exploration company in the remote Northern Territory desert, when he was involved in an industrial accident which put him in the Tennant Creek hospital for an extended stay. When he was next in Brisbane, he told me that he had really developed a liking for morphine whilst in hospital.

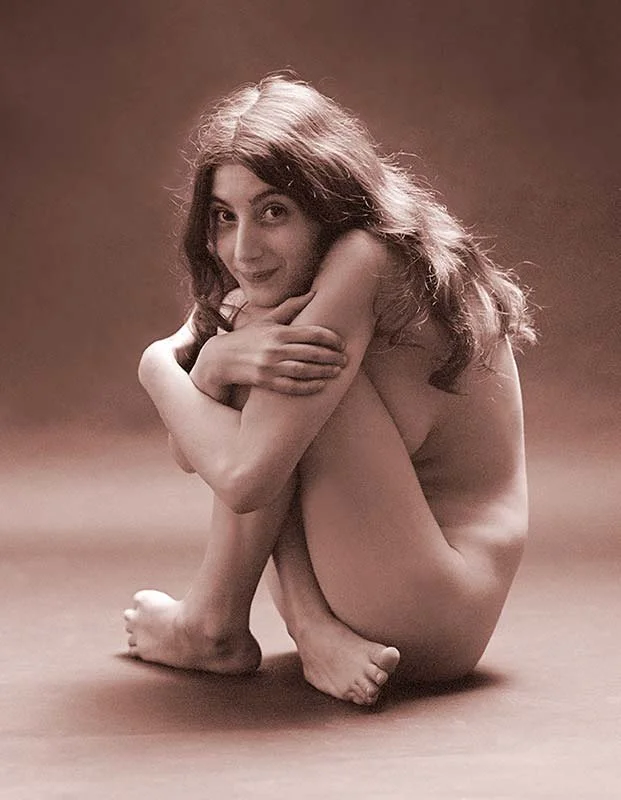

During happier times, from the late 1960s, Mike helped run a very successful leather-craft shop in Maroochydore, on Queensland’s Sunshine coast. It was here that he met and fell in love with a very beautiful girl, Susie.

Susie

He also found spiritual peace through guru Meher Baba, who did great charitable work in establishing hospitals and educational facilities in India. Mike's favourite Baba quote was “He who knows does not speak, he who speaks does not know”.

His next move was to Sydney, where he ran a successful screen-printing business producing street posters for musical gigs. At the same time, his fondness for opiates had taken another turn. The next time I met up with him, he told me “Jimi Hendrix was right, not the first stone, but beautiful”. He had developed a full addiction to heroin.

I was initially quite angry with him, but understood that the world’s most effective pain-killer was what he needed to shut out the past. He got out of the screen-printing business, and started driving Sydney cabs for a living. “I drive the cabs to make the money to buy the smack to have the courage to drive the cabs…”.

Eventually, Mike moved to Western Australia, where he was working as a short-order cook. He met a girl with whom he would eventually settle down, break free of his heroin habit, and have a beautiful little daughter. The next time I caught up with him was on one of my infrequent visits to Brisbane, where he and his little family were then living. He looked so fit, happy and healthy. His life had a purpose. He had taken up banjo playing, for which he had a real talent. He was a big fan of Zydeco music, in particular the work of “The King of Zydeco” Clifton Chenier.

Over the years, we always stayed in touch by telephone. One night, he told me that he’d been diagnosed as having Hepatitis C, a legacy of his heroin days in Sydney twenty-odd years previously. This would eventually lead to cancer of the liver. His marriage ended acrimoniously, and he was denied access to his daughter, something which broke his heart.

He then moved to Stradbroke Island, in Brisbane’s Moreton Bay, and became the local cab driver. During our customary long-winded phone-calls, Mike kept me updated on the progress of his illness. A few years later, I made a visit to Brisbane, where we arranged to meet for dinner. I arrived at the fairly crowded restaurant, and scanned the room looking for Mike. My Brisbane-based son was with me, who quietly said “That’s Mike, Dad” and led me over to meet my wonderful old buddy. I don’t think I did a very good job of hiding my shock at his totally emaciated, greyed appearance. Inside that dying body was the same alert mind, the lover of great literature and music, the huge intellect. We had a great evening of conversation, covering every topic we could cram in.

Within a few months, Mike slipped away. He had knowingly trodden the path of unsafe drug use, finding a panacea for his traumatised past, and it cost him his life. Sadly, he was a few years too early to receive the modern, successful treatments that are now available for Hepatitis C sufferers.

Rest in peace, old genius mate.